Hate and harassment in gaming spaces take a toll on the mental health of the community. From short-term distress, to long term post-traumatic stress disorder symptomology, we know that these actions negatively impact direct targets of these behaviors as well as any third-party bystanders. While this certainly makes a case for the ethical need for better moderation, stronger community guidelines, and greater transparency from gaming companies, it has done little to empower industry action. While many members of the gaming industry care deeply about these challenges, they do little to motivate bottom line-focused executives. As such, it is nearly impossible to enact change without demonstrating its direct impact on the bottom line.

So, we set out to answer this question: how does toxicity impact the bottom line?

This year, we gained the first insight into how toxicity and revenue are related. Looking at game players aged 13 – 25, researchers found that the average monthly amount of money spent on games deemed “non toxic” as compared to “toxic” was a difference of 54%. That is, there was a 54% gain in revenue for games that “don’t sell consumers spewing name calling, racial epithets, holocaust denial, misogyny, threats to one’s safety, and your garden variety rape and death threats” (p. 1).

Building on this work, Take This collaborated with Nielsen, a global leader in data and analytics, to further examine the relationship between toxic communities and revenue. We polled 2,328 adolescents and adults residing in North America about their experiences with gaming communities to examine the impact of toxicity on spending and engagement behaviors.

Nielsen collected this data through their Video Game Tracking Service and provided it to Take That through its Data for Good program. If you’d like to learn more about VGT and how you can leverage it reach out to vgtinfo@nielsen.com

6 out of 10 players said they had, at least once, quit a session or match or quit a game completely because they were subjected to hate and harassment within that gaming community.

6 out of 10 players reported they had, at least once, chosen to not spend money in a game because of how other players treated them in that community.

7 out of 10 players reported avoiding playing certain games because of the reputation of the community.

Younger players (under 18) were also found to be more likely to take action against toxic gaming communities (i.e., leave a game, not spend money, or not engage in a gaming community at all because of its reputation).

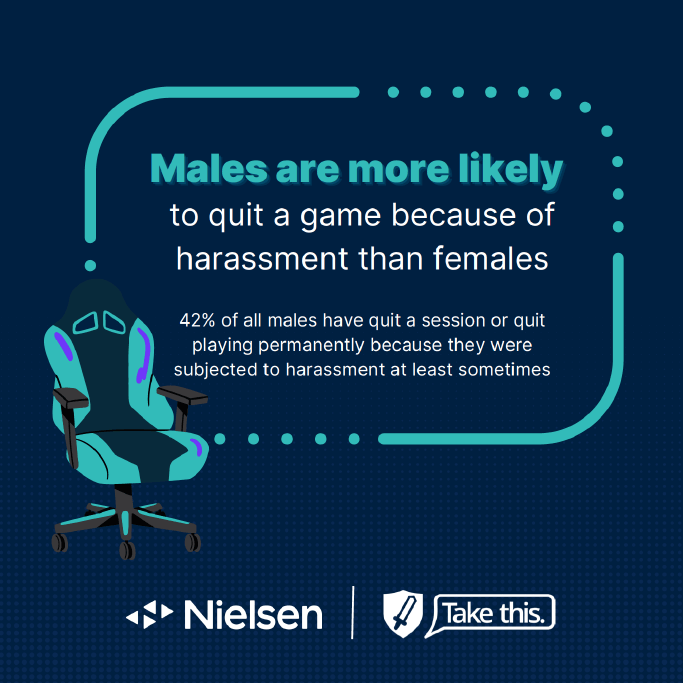

However, perhaps the most surprising finding was that male players were more likely than female players to report a change in their spending and playing behavior due to toxic communities.

These findings demonstrate that toxic communities impact the bottom line in broad, negative ways. Players are not spending as much money, players are not spending as much time, and players are choosing to not even engage in certain gaming communities because their reputation precedes them.

While the ethical argument for less hateful gaming spaces is an important one, and one we will continue to discuss, demonstrating a business case for reducing hate and harassment is a significant step in empowering the industry to make more sweeping changes for gaming spaces to be less-hateful, and less-toxic environments.

A full report of these findings is currently under review for publication.

Dr. Rachel Kowert (@DrKowert) is the Research Director of Take This. She has been studying the uses and effects of digital games for more than 10 years. To learn more about Rachel and her research, visit www.rkowert.com